The expression “Don’t quit your day job” is often used as an insult, implying that the recipient’s creative skills aren’t up to attracting a career-supporting audience. But it can also be practical advice in certain cases, especially those of artists possessed of a sensibility too particular and strange to bear direct exposure to the marketplace. So it was with Henry Darger, who deliberately passed his 81 years in near-absolute obscurity, working increasingly menial janitorial jobs by day and, when not attending one of his five daily masses, obsessing over his art the rest of the time. That art took various forms, most notably The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco–Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, which has been described as the longest work of fiction ever written — and the strangest.

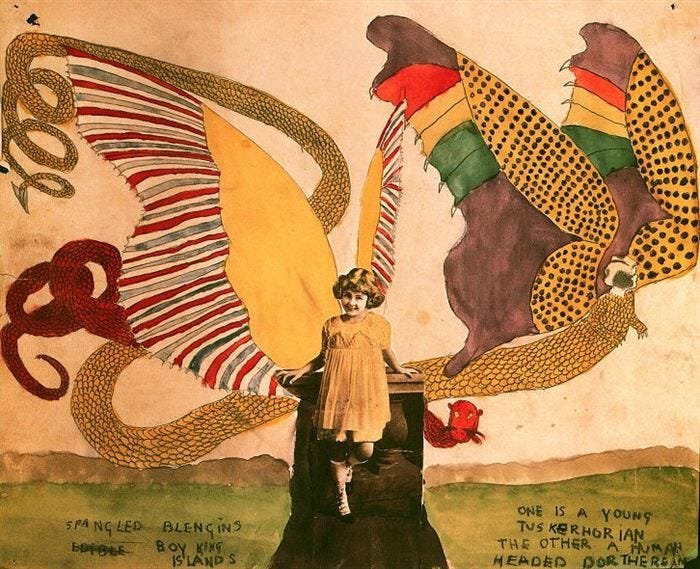

As described in the video above from Fredrik Knudsen (and in the 2004 feature-length documentary In the Realms of the Unreal), its 15,145 pages relate the adventures of a set of immaculately virtuous little girls against the backdrop of an apocalyptic, ultra-violent religious war. When Darger’s landlords discovered the work after his death, they also turned up a variety of drawings, paintings, and collages, many of them at least obliquely related to the story.

Against backdrops alternately idyllic and harrowing, the Vivian girls often appear naked, sometimes bewilderingly outfitted with male genitalia. Though clearly composed without formal training of any kind, Darger’s visual compositions demonstrate an askew kind of proficiency, or at least a kind of staggering evolution over the course of decades. Whatever the appeal of his work, there’s never been an artist like him. Nor could there be, given the highly specific stretch of history occupied by his long yet rigidly bounded life.

Not long after Darger’s birth in the Chicago of 1892, the death of his mother followed by the incapacitation of his father plunged him into a childhood of Dickensian-sounding hardship, spent in institutions with names like the Illinois Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children. An aggrieved loner seemingly afflicted by what we would now call mental health difficulties from the start, he took a kind of refuge in the fantasy cohering in his head, one shaped equally by mass print media phenomena like Winnie Winkle and Little Annie Rooney, Civil War photographs, and ultra-devout Catholicism. Since his posthumous discovery and elevation to the status of the ultimate “outsider artist,” there’s been no end of speculation about his personal habits, sexual proclivities, and state of mind. But with all such questions beyond resolution, we can, for the moment, leave the last word to the artist himself: “It’s better to be a sucker who makes something than a wise guy who is too cautious to make anything at all.”

Related Content:

Explore a Digitized Edition of the Voynich Manuscript, “the World’s Most Mysterious Book”

Lewis Carroll’s Photographs of Alice Liddell, the Inspiration for Alice in Wonderland

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He’s the author of the newsletter Books on Cities as well as the books 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea) and Korean Newtro. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.