“Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get.”

The line from Forrest Gump is meant to capture uncertainty in love and life, but every Valentine’s Day, it accidentally describes markets just as well. Chocolate prices rise, products take different shapes, and consumers are surprised once again at the checkout line. The usual explanation immediately turns to corporate greed. Yet what Forrest Gump’s chocolate box really reminds us is that uncertainty, timing, and expectations shape outcomes, and that prices exist to navigate uncertainty, not to exploit it.

Xocolātl, the beverage we now call chocolate, originated in tropical Mesoamerica, across what is today Mexico to Costa Rica. Before it became a sweet confection, xocolātl was a bitter mixture of cacao beans, water, and spices, cultivated, traded, and consumed for elite, ceremonial, and everyday uses. Only after 1492, through the “Columbian Exchange,” a term coined by Alfred W. Crosby, did cacao enter the wider Atlantic economy, where ingredients, capital, and know-how recombined across continents. New World cacao met Old World sugar, dairy, and manufacturing, and the modern chocolate industry was born.

Although centuries removed from the Maya and Aztec civilizations, chocolate remains a symbol of affection today. The transatlantic transformation of cacao into chocolate, combined with medieval courtship traditions, helped produce Valentine’s Day as we know it. Last year, among the cards, flowers, and jewelry, Americans bought 75 million pounds of chocolate or roughly the weight of 15,000 elephants. For 2026, the National Retail Federation and Prosper Insights & Analytics project record spending: “Consumer spending on Valentine’s Day is expected to reach a record $29.1 billion…surpassing the previous record of $27.5 billion in 2025.” Record spending, however, is often mistaken for evidence of record prices. When prices rise, many are quick to draw back their bow and let their arrow fly even when the true source of higher costs lies elsewhere.

Rising prices around holidays are often attributed to a familiar story of corporate tricks, rather than treats, known as “greedflation.” Supermarkets and chocolate companies are accused of exploiting a sentimental holiday, padding margins under the cover of romance. In recent years, this narrative has resurfaced almost reflexively whenever grocery prices rise. However, retailers do not set prices in a vacuum; they respond to constrained supply and higher input costs. To understand why chocolate costs more, we need to look past the supermarket aisle to the governments and growing conditions that shape the cocoa market itself.

The International Cocoa Organization notes that roughly 70 percent of cocoa is produced in Africa, with Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana leading output at about 1,850 and 650 thousand tons, respectively, in 2025. Cocoa is central to both economies, accounting for about 15 percent of Côte d’Ivoire’s GDP and seven percent of Ghana’s GDP. In 2018, the two nations formed the Côte d’Ivoire–Ghana Cocoa Initiative (CIGCI), informally referred to as “COPEC.” Its stated aim is to correct perceived market failures by raising prices: “Without correcting the many market failures, the cocoa economy is destined to become a counter-model of sustainability.”

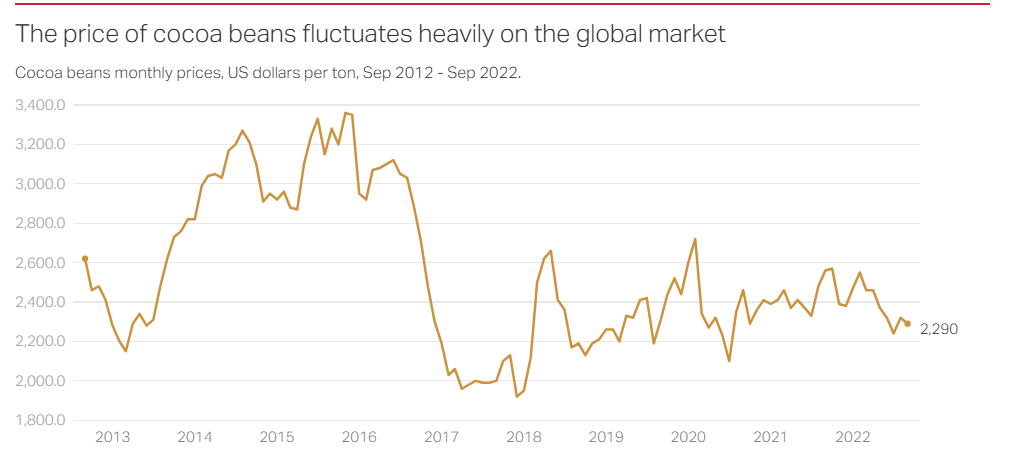

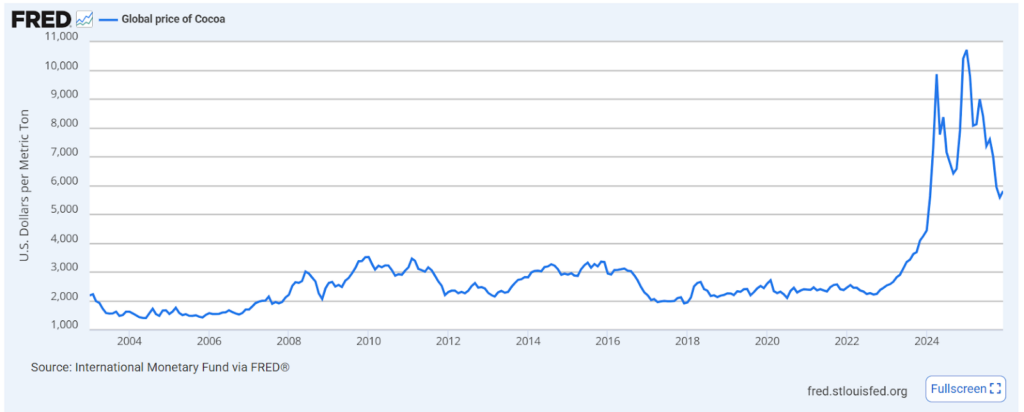

Switzerland’s national broadcaster, SWI, documents a sharp price movement beginning in early 2018, coinciding with the cartel’s creation, suggesting that coordinated policy had immediate market effects.

According to World Finance, COPEC may also have served domestic political goals, with promises of higher prices timed around election cycles to win farmer support. Regardless of motivation, both countries have announced higher prices for the 2025/26 crop season. Côte d’Ivoire will raise prices by 39 percent, which pales in comparison to Ghana’s 63 percent price increase.

These administratively set prices add to a system already strained by corruption within Ghana’s Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) and black-market activity in Côte d’Ivoire. Highlighting growing smuggling operations, Ivorian authorities last year seized 110 shipping containers, about 2,000 metric tons, of cocoa beans falsely declared as rubber, worth $19 million. From the report:

The tax on this shipment should have been 19.5 percent, including the 14.5 percent tax on cocoa exports and the five percent registration tax. In that case, the Ivorian state would have collected 2.9 million pounds in taxes. Meanwhile, the tax on rubber exports is only 1.5 percent.

Needless to say, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana have constructed a highly interventionist system around their most important export. Compounding these policy distortions, the 2025/26 crop season is expected to see a 10 percent fall in output due to “shifting weather patterns, ageing tree stocks, disease, and destructive small-scale gold mining.” This shortage has intensified pressure in an already volatile cocoa market. According to FRED, cocoa prices have risen by more than 70 percent in the last five years.

Last year, North America’s largest chocolate producer, Hershey, announced price increases across household names such as Reese’s, Kit Kat, and Kisses: “It reflects the reality of rising ingredient costs, including the unprecedented cost of cocoa.” In the earnings Q&A call on February 5, 2026, CEO Kirk Tanner stated, “Our actions…are anchored in consumer insights and the brands remain affordable and accessible. Seventy-five percent of our portfolio is still under $4.” Tanner framed their strategy as keeping products as affordable and accessible as possible despite rising cocoa costs.

Given cocoa price volatility, Hershey’s effort to keep chocolate affordable, and supermarket margins of just one to three percent, “greedflation” melts away like a chocolate kiss on Valentine’s Day — leaving scarcity and policy, not corporate greed, as the real culprits. The bitterness in chocolate prices comes from constraints and institutions, not from greed.