On Friday, the writers of this site lauded some of their favorite performances of 2025. Today, we go behind the camera to pick some of the great craft of the year in film, including excellence in cinematography, editing, original score, casting, and more. Again, this shouldn’t be seen as comprehensive as much as a way to highlight some of the people who made us love movies this year. Enjoy.

Cinematography, Anthony Dod Mantle, “28 Years Later”

It was always going to be impossible to match the visual audacity of “28 Days Later,” which memorably shot its doomsday outbreak in the haunting fuzz of early digital. Photographed by the legendary Anthony Dod Mantle, it wasn’t just that Danny Boyle’s zombie-adjacent thriller almost looked like found footage, it was that the images themselves seemed tainted, forever on the brink of self-deletion. So it’s all the more remarkable that “28 Years Later,” a legacy sequel with unexpected beauty and terror, comes so close. The style may be less brazenly iconoclastic, but Boyle, reunited with Mantle, discovered a new language of digital horror yet again. Swapping the Canon XL1 for an iPhone 15 on an assortment of how-did-they-do-that camera rigs, anywhere Boyle wants to put the wide-lensed cameras, he does; the shoulders of new burly infected, the back of drones zooming at head-twisting angles around our protagonists Spike and Jamie, and below the ground as infected bloodily smash their faces into the lens.

More singular is the horseshoe shaped rig outfitted with 20 iPhones, which lets the visual frame jump through multiple angles with disorienting, time-blurring speed, highlighting kill-shots with frenetic rapture. Despite the carnage, there’s jaw-dropping beauty, too. Few scenes this year matched the mythic awe of the mid-film footchase under a canopy of aurora borealis, a crescendo to the way Mantle reminds us that horror needn’t be frightened of color. All these flourishes may seem gearheaded and extreme, but they only ever bring you closer to young Spike’s harrowing journey. In a year full of visual achievements, 28 Years Later is among the very best. –Brendan Hodges

Stunts, Wade Eastwood, “Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning“

The stunts in the Mission: Impossible movies — especially ones by Tom Cruise himself—were always the best reason to check out new entries in the series, even more so after Cruise partnered with writer-director Christopher Quarrie and morphed into a spiritual descendant of Jackie Chan and Buster Keaton. The third point in the creative triangle that gave the Cruise-McQuarrie movies a distinctly different flavor was Wade Eastwood, stunt supervisor and sometime second unit director, who joined the Impossible Mission force with “Rogue Nation.” The series’ concluding chapter “The Final Reckoning” might’ve gone overboard with super-specific callbacks to every other entry, in a forced attempt to tie them together retroactively; nobody goes to action movies for plot, after all. But the movie was aces in the “let’s see how close we can get to killing our leading man” department.

The long sequence in which the US Navy gives Ethan permission to use a Virginia-class submarine to reach the sunken Russian submarine Sevastopol is so precisely staged and directed, each thrill bigger than the last, that it almost feels like a movie-within-the-movie. Ethan’s encounter with a Russian sailor who turns out to be a minion of The Entity –the Borg-like sentient A.I. that wants to absorb everything and everyone —is classically simple, just two guys trying to kill each other in a tight space. The horror movie lighting and camera angles prepare you for the most shockingly primal violence in the series. It’s less spectacular than the three-way bathroom slugfest in “Fallout,” but more disturbing for how vulnerable Ethan seems, fighting a deranged, fully uniformed adversary with a huge knife while unarmed and clad only in shorts and barefoot shoes.

That such a relentless Mano a Mano is intercut with a close quarters shootout between commandos and the rest of Ethan’s team in a burning house raises the whole section to the level of the sublime. But it’s all a warmup to Ethan trying to escape the Russian sub as his oxygen is running out AND the craft is flooding AND tipping over the edge of a cliff. The payoff is one of the most eerily beautiful “Oh, no, is he really dead?” scenes in the series: Ethan, nearly naked in freezing water, swims to the surface through sheer will, only to run out of air just as he’s about to touch a thick sheet of ice that would’ve prevented him from surviving anyway.

Cruise, McQuarrie, Eastwood, and their army of collaborators send us off with a shoutout to the earliest years of action cinema, the silent period right after World War I, in which planes were huge lawnmowers with wings, and the idea of taking flight was unnerving in itself. You’ve seen a few aerial dogfights in your time, but never one that makes you so keenly aware of how speed, height, wind resistance, and a limited fuel supply factor into the tactics of biplane pilots dueling in the sky. Those lucky enough to see “The Final Reckoning” on a large-format screen with bone-rattling sound will testify that watching the final act was like being on a ridiculous and terrifying roller coaster that went full speed for an hour straight and sent viewers stumbling into the lobby, dazed and happy.–Matt Zoller Seitz

Original Score, Nine Inch Nails, “Tron: Ares”

Despite our very own Matt Zoller Seitz’s adulation, some have quipped that the best way to enjoy “Tron: Ares” is to view it as a 119-minute music video for a new Nine Inch Nails album. I’m warmer on the film than most, but I also find the score to be the film’s standout. It’s fittingly heartwarming to be reminded that even when corporate thinking means that a franchise like “Tron” is to be milked, true art can emerge from such cash grab-fueled madmen.

Indeed, the propulsive and gritty score for “Tron: Ares” courses with too much personality to fully convince me this was created via commission. Then again, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross–even when they’re not releasing music under the band name’s moniker–were never ones for subtlety. Vociferous may be par for the course for this duo, who famously turned the tennis courts in New Rochelle and NYC sewers into dance floors, but there’s something distinctly soulful and human in the duo’s compositions for Joachim Rønning’s film that makes this all feel more than just noise. It feels as if they tried to make a score that the film would have to bend around to accommodate, rather than the other way around.

Take the darkwave track “Target Identified,” whose sinister synths make the feeling of being targeted by evil AI programs feel exhilarating. The opening track “Innit” feels less arranged and more haphazardly thrown into the film like an identity disc; it makes sense for it to play over the film’s opening credits because words are the only thing that can keep up with its momentum. There’s also “Infiltrator,” which feels as though it belongs as much in the club as it does in the cinema, hilarious given that the scene it plays over is that of an antagonist AI trying to stealthily–well, infiltrate–a database. The score is definitely raucous and in contrast with the scene, as if Reznor and Ross are challenging the film’s creative team to warp their idea of a clandestine heist into something much more operatic and epic.

For a film that interrogates the artifice of identity and the virtual worlds we create to absolve ourselves of the pain of living in the real one, it’s befitting that “Tron: Ares” feels so enveloping, as if it’s trying to capture you and bring you into its artificial world. As the world tragically embraces the inadequate artistic facsimile created by algorithms, ironically, within a story that tries to proselytize about embracing AI, Nine Inch Nails have crafted a soundtrack that speaks to the enduring unpredictability and singularity of the human spirit. It’s as if the duo predicted the hellscape we might find ourselves in 2025 and decided that if democracy were to fall, at least it could be heralded with thunderous bass. –Zachary Lee

Choreography, Celia Rowlson-Hall, “The Testament of Ann Lee”

“The Testament of Ann Lee” highlights the expressive, integral nature of choreography. A thrill, considering the work of choreographer and filmmaker Celia Rowlson-Hall, which is so stunning in its execution. For a film that traverses the life of a woman who seeks a higher calling, the choreography makes sure to tether itself to the earth. The movements start low before going aloft, a visual echo of Ann and her followers. The act of prayer is a physical one, from the bruising way Ann thumps on her chest, to the hunched shoulders and pounding fists on ship decks.

There’s also an unexpected playfulness to Rowlson-Hall’s work. Take, for instance, the carnal energy of the group prayer, as the followers move together in a physical expression of intimacy, even as they choose abstinence to prove themselves wholly devout. But it’s how the bodies contort themselves throughout each number that spells brilliance, demonstrative of the convergence of prayer and dance. Be it the intimacy of “Hunger and Thirst,” which simply follows Ann in one of her lowest moments, awakening to a new day through repetitive gestures, to the early waltz through the woods, and the human wave of the Shakers as their bodies pulsate with unmitigated zeal, moving in one long, thrumming motion, the dancing is mesmerizing. We, like the dancers, lose ourselves in it. Rowlson-Hall doesn’t waste any gesture, each step, each flex of the hand, brimming with intent. –Ally Johnson

Original Score, “One Battle After Another”

A central tenet of Paul Thomas Anderson’s paean to preposterous radicalism is the notion of ocean waves. They appear in the mantra-like sentiments of Benicio Del Toro’s sensei figure, are visually exemplified by the stunning long-lens look at a ribbon of highway bisecting the desert sands, and they are heard through the vertiginous soundscape that Johnny Greenwood has assembled.

It’s hardly a surprise that Radiohead’s guitarist would provide a blend of symphonic lushness with percussively kinetic soundscape to a PTA vehicle, but this collaboration may prove both the most sophisticated and satisfying to date. While RogerEbert.com’s esteemed editor Brian Tallerico playfully described the compositions in “One Battle After Another” as being “bonkers,” there’s method to this compositional madness, with the flurry of pianistic notes and drone-like asides, acoustic and synthetic alike, sweeping in and out like waves crashing ashore. The result is a mix of power, chaos and bouts of repetition, the latter that lulls one into a daze whilst an almost subliminal growing anticipation bubbles below, as we tense up for the next tidal and tonal change to come.

Beyond Greenwood’s Varèsian bombast and Schönbergian orchestral sophistication, there’s a rock-and-roll ethos still peeking through some of the score’s crunchier, punk-like moments. There are dialectical collisions of both temporal and timbral elements (drawing from the likes of Frank Zappa’s concept of xenochrony) that makes has these turbulent sonic waves as vital to the success of the storytelling as any other aspect.

Throw in some welcome additions including unearthed explorations between PTA and John Biron, as well as a killer needle drops from The Jackson 5, Ramsey Lewis, Ella Fitzgerald, The Shirelles, Gill Scott-Herron and, of course, Steely Dan (whose “Dirty Work” helps form much of the chordal bedrock for Greenwood’s explorations) and you’ve got one yet another mind-blowing playlist from one of the most legendary soundtrack-crafting partnerships in cinematic history. –Jason Gorber

Cinematography, Pär M. Ekberg, “Black Phone 2”

Scott Derrickson may have his bad days, but very few directors have his good days. 2012’s “Sinister” created an expectation that he can tell a horror story through the visuals alone, with the properly calibrated jump scares and truly haunting 8mm interludes. On his good days he produces a texture that turns America’s false idyllic domestic past into a place of unruly horror. “Black Phone 2” is his best film when reduced to what the camera shows us, and in this case it’s a killing spree but a demented satyr, a killer in the woods with a hatchet turning children into cautionary tales with each jittery frame. Meanwhile, the narrative camera, in agoraphobic 2.39:1 widescreen, allows us to see monsters everywhere against the blue white of snow. The hokey-est ideas become otherworldly when bathed in Pär M. Ekberg’s cool, bleak lighting. The music video veteran treats each scene like a short film, giving the film raw power with every visual opportunity. No other film this year looks like “Black Phone 2,”and a good deal more should try. –Scout Tafoya

Cinematography, Christopher Messina, “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You”

In the psychological dark comedy “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You,” director Mary Bronstein throws the viewer directly into the turbulent life of a therapist named Linda (Rose Byrne, in a career-defining performance), as she juggles the chaos of an unwell patient, a hostile relationship with her own therapist, an absent husband, a house that has been torn apart by a giant hole in its roof, and the unnamed illness of her daughter that requires round the clock care and feeding through a tube. As they began filming, Bronstein told her star that the aim was to film as if they were in Linda’s eyeballs for the duration of the movie. Working in tandem with cinematographer Christopher Messina, this was achieved with extreme close-ups on Linda, often leaving everything out of the frame except her often-distressed face.

Throughout the film Linda’s daughter is not seen, although she is heard, remaining a small, often annoying voice, just out of the frame. Although she stays entirely off screen for most of the film’s runtime, her wants and needs somehow dictate Linda’s entire life. Even the red light of her feeding tube at night becomes an oppressive force that engulfs their entire hotel room. This notion that we are inside Linda’s eyeballs goes one step further in one of the film’s flights of fancy as Linda visits the gaping hole in her apartment one night. The thick blackness of the void swirls and grows before Linda’s eyes, while every thought and memory inside her head, past and present, collide in a cacophony of sound and fury. The result is a film that is at times viscerally uncomfortable to watch, the ultimate filmic embodiment of walking a mile in someone else’s deeply stressed-out shoes. –Marya E. Gates

Adapted Screenplay, James Gunn, “Superman”

Superman is among the most valuable IP characters in the world, but that value, at least in movie terms, has come with a massive asterisk for a shockingly long time. What value does a character truly have if seemingly no one can get him right? That question had plagued Warner Bros. for over 40 years, as the last half dozen Superman movies have been either achingly boring (“Superman Returns”), campy schlock (“Superman IV: The Quest for Peace”), or woeful misunderstandings of the character’s core appeal (the gloomy destruction-porn of “Man of Steel” and its sequels). That’s the catch-22 with an all-powerful character who’s meant to be a shining beacon of hope and aspiration—how to concoct a credible threat to the former without sacrificing the latter.

I was admittedly dubious of whether James Gunn was the right choice for a long-overdue course correction. Despite loving his “Guardians of the Galaxy” movies, I worried Gunn’s tongue-firmly-in-cheek style might be just as much of a mismatch for the original superhero as Zack Snyder’s joylessness was. Happily, I was very wrong.

Gunn succeeded in the most unlikely of ways. Instead of trying to import Superman into the realism of our awful world, Gunn exported the threats we face in 2025 America to the bright, comic-book world of Metropolis. How would a physically omnipotent hero combat right-wing grievance media, internet deep fakes, social media disinformation, and a public that’s become addicted to being lied to by bad-faith billionaires? Those are threats worth watching a Superman movie about and seeing them defeated was as contagiously inspiring and hopeful as a Superman movie should feel. “Superman” got a lot of things right, from its bright visuals and hilariously misbehaved Krypto, to the most perfectly-cast Lois, Clark, and Lex we’ve ever had. (Yeah, I said what I said.) But first and foremost, “Superman” succeeded at a basic story and character level, because James Gunn understood the assignment. –Daniel Joyaux

Casting, Jennifer Venditti, “Marty Supreme”

Casting director Jennifer Venditti’s work started with the Safdie Brothers for 2017’s “Good Time,” and she’s been working with both of them ever since. Her greatest claim to fame is the collaborative casting of “Euphoria,” which introduced the world to some of the most famous young performers in Hollywood. The argument can be made that Josh Safdie had already met with Timothee Chalamet about “Marty Supreme.” He’s certainly central to the overall success of the picture. But that would also be shortchanging some of the most exciting casting choices of 2025.

Gwyneth Paltrow certainly doesn’t act as often as she used to, given her wellness and lifestyle brand, Goop. Her business savvy and personality have overshadowed her acting abilities, as she’s terrific as the retired actress Kay Stone. Finding Odessa A’zion for Rachel was a stroke of genius, as she’s about to launch into the stratosphere on HBO’s “I Love LA.” She could easily find herself in the Best Supporting Actress mix this year. Tyler Okonma (Tyler, the Creator) has appeared in TV shows before, but has often played himself. Here, he seamlessly inhabits the role of Chalamet’s trusted ally. The final bit of inspired casting comes from including Kevin O’Leary as a cruel businessman. O’Leary’s personality has brought him success on TV’s “Shark Tank,” but this is his first film performance, and he’s certainly up to the task. This list hasn’t even gotten to shout out Abel Ferrara, Fran Drescher, and Koto Kawaguchi. Venditti collected an inspired cast to bring the story of Marty Mauser to life, and it’s certainly among the year’s best. –Max Covill

Original Score, Daniel Pemberton, “Eddington”

The music in each of Ari Aster’s feature films has always felt like a character. Working with musician Bobby Krlic since his sophomore feature “Midsommar,” Aster’s newest film “Eddington” saw Krlic collaborating with composer Daniel Pemberton. While the two have very different techniques, their contrasting styles allow the film to unravel into a haunting mishmash of ideas and sounds, reverberating ominously through each minute of the film’s 2 hour and 28-minute runtime. Pemberton’s work dominates through the first few scenes of the film, where he utilizes soft strings that perfectly blend with the apparent righteousness of the film’s small town. Then comes Krlic’s first solo track, “Slogan Ideas,” where the classical Hollywood feel dissipates, giving way to heady guitar strings found in old westerns.

From there, both Pemberton and Krlic blend modern sounds with echoes of American cinema’s past, creating a unique soundscape that feels tethered not only to Eddington, New Mexico, but the fracturing psyche of the film’s characters. The film showcases a perfect blend of what both of these composers do best, the score humming and whining just as its characters do, before exploding into a cacophony of dueling sounds with one of its final tracks, “Here Comes the Cure.” In “Eddington,” the score is just as at war with itself as Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix) and Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal) are at war with each other, plucky strings and crescendoing horns allowing the horror of America’s broken spirit to take root.

Production Design, Alexandra Schaller and John Lavin, “Train Dreams”

There is already much earned praise that has been bestowed upon Adolpho Veloso’s stunning cinematography in “Train Dreams,” but there should be just as much celebration of the rich production design that brought the film’s world to life. Alexandra Schaller and John Lavin, two longtime veterans of their craft, have built a world that feels like you can reach out and touch it while watching it. From every detail of the lovingly made cabin that the sweeping film’s lonely Robert Grainier initially lives in with his family before residing there alone when he loses them to the massive firewatch tower that was actually built on the side of a hill, this is a film whose each and every element are ones that you almost don’t even notice because of just how natural it feels.

This is a testament to the work of Schaller and Lavin, who, with their talented fellow crew, even built some of the trees we see in the forest. That shot with the man lying inside a tree? That was built from the ground up. The train Robert watches making its way along the tracks he’s just built for a country that will soon leave him behind? They built that. The plane in the breathtaking final frames where Robert sees his small world from the sky? They built that on a gimbal on the ground to simulate the weightless feeling of flying high. To quote William H. Macy’s character from the film, it’s beautiful, all of it. – Chase Hutchinson

Original Score, Rob Mazurek, “The Mastermind”

In “The Mastermind,” Kelly Reichardt diverts ever so slightly from her typical, slow cinema storytelling. This “art-heist” film is Reichardt’s “One Battle After Another.” She, too, reckons with a deadbeat dad navigating an increasingly hostile political America; “The Mastermind” is existentially action-packed. While the plot itself is stressfully silly, the jazz-forward score decorates that tension with excitement and emotion.

The abstractavist, Rob Mazurek, is near flawless in composing his first-ever feature film score. His Chicago-based roots shine through, understanding the right amount of calculated improvisation to manipulate how the audience feels. As the main character, J.B. (Josh O’Connor), moves westward, the score becomes increasingly wild. Music moves the film’s pacing in a smooth, playful manner; there is more pizzazz when there is more at stake.

While I feel inclined to say the music mirrors the actions of J.B., upon rewatch and relisten, the sonic structure is so strong and entangled with enhancing the visuals that it’s uncertain who is in control. Perhaps that is the point, like jazz, it’s free-flowing, adapting, taking risks, and keeping everyone (most importantly the self) entertained. I am always pleasantly surprised by how it moves through moments of melancholy and bounces back to life.

Cinematography, Steven Soderbergh, “Presence”

I can’t recall a time when I wasn’t struck by the cinematography of a Steven Soderbergh film. It’s not only the camera’s movement and framing, but the color palette, and the way he bounces the cinematography off other aspects of the craft, like editing and music. It’s also the way in which the cinematography is an expression of the film’s soul, articulating with precision its persona, whether it’s the grittiness of “Traffic,” the playfulness of “Out of Sight” or the coolness of “Ocean’s 11.” With “Presence,” Soderbergh once again displays his dexterity by creating an entity POV film.

There is no shortage of theories about the role of the camera: from a tool to photograph the action, to an extension of the audience’s gaze, complicit in the voyeuristic act. In “Presence,” everything we see is from the ghost’s POV, and here lies a fascinating tension. The POV might adopt a voyeuristic gaze, watching up close the family’s day-to-day lives, but it’s they that are intruding on the ghost’s personal space. They force it to play the role of voyeur. This elicits a sympathy for the invisible protagonist. Just as we read the actor’s body language, so the camera movements inform our impression of whom this mysterious entity is. The shyness in the early scenes, when it hides from the family, its growing curiosity and the emotional outbursts all serve to reveal its character. What remains special about “Presence” is that Soderbergh somehow creates a character through cinematographic suggestion alone. –Paul Risker

Original Score, Kangding Ray, “Sirāt”

Often, the best film scores touch the heart or stir the spirit; this one, you feel deep in your bones—which perfectly suits Oliver Laxe’s fever dream of a fourth feature, which opens with a father searching for his lost daughter in the mountains of Morocco before descending into the desert to become a sonically mesmerizing work of metaphysical terror. Set in a remote rave culture that hosts illegal parties far from civilization—all deep, throbbing bass that reverberates through the battered, sometimes broken bodies of attendees, their movements suggesting a subconscious trance between agony and ecstasy—“Sirāt” benefits immensely from the interplay between its intensely atmospheric sound design and Kangding Ray’s sensational electronic score. With its textural density a driving force throughout the film, the French club musician’s compositions slowly transition from electrifying, psychedelic waves of sound to more skeletal, stripped-down arrangements, mirroring the way that Laxe’s narrative—which leads its potentially doomed characters through all manner of harrowing and horrifying ordeals en route to an uncertain destination—disintegrates like a sculpture crumbling into dust, blowing away in the desert’s howling winds. Ultimately, Kangding Ray’s score is revealed to be, more than simply a sonic landscape that immerses the viewer in the film’s rave scene, itself a kind of auditory bridge between heaven and hell, suspending the film’s atmosphere in a purgatorial state of divine, deafening bliss. –Isaac Feldberg

Costume Design, Kate Hawley, “Frankenstein”

Guillermo Del Toro had a simple directive for “Frankenstein”: “I want people painting, building, hammering, plastering.” Costume designer Kate Hawley listened and the results are visceral.

First, color: carnelian red for Claire, a mother’s love worn on her sleeve; upon her death, Victor keeps a red scarf around his neck, often donning red leather gloves too, his mother’s spilled blood literally guiding his actions and decisions. Harlander’s tight tan gloves and nymph-topped cane reference his need for control, perhaps even the source of his illness. Adult Victor dons neither Dickensian nor Victorian attire, but an 1850s blend of David Bowie’s Thin White Duke era, Mick Jagger, a little Francis Bacon, and Rudolf Nureyev. Hawley stopped fixing Isaac’s costumes between takes, saying, “He had lovely clothes, but…wore them irreverently. To me, that is the ultimate kind of rock star language.”

Garments for Elizabeth establish her relationship with nature: her malachite and magenta crinoline dresses, overlaid with tulle, were hand-printed to mimic blood cells and the iridescent shells of beetles. Diaphanous materials (the organza veils and sheer, 1960s Victorian horror nightgown) are multipurpose: they constantly shift color to evoke the evanescence of God’s creation, they reference Claire, but also the dreamlike nature of memory, of repetition as a part of the storytelling. Elizabeth’s carnelian red rosary (the cross has a beetle inside) and blue scarab beetle necklace—in keeping with Claire as a callback and nature as a vital force, respectively—are archival Tiffany pieces.

It is Elizabeth’s bond with nature and God that creates her rapport with the Creature. The Creature is a composite of parts from fallen soldiers, as are his clothes; he must cobble a self together at every turn, literally and figuratively imprinting on his person the memories of those whose limbs and garments he now uses. Elizabeth’s wedding gown is a final reunion between herself, the Creature, and Claire: the Swiss ribbon bodice harkens back to “The Bride of Frankenstein,” but also references the strips of bandages hanging from the Creature’s frame. Each layer of the gown, like Elizabeth’s other dresses, functions like an X-ray, revealing layers of filleted skin, and once she is maimed, blood blooms inside the bodice, evoking Claire’s color motif and her death. The best costume work tells a story without dialogue, and Hawley’s work speaks volumes. –Nandini Balial

Cinematography, Dong Jingsong, “Resurrection”

Shooting Bi Gan’s “Resurrection” meant shooting six films in one, using six different styles and color palettes to evoke not only five different periods in cinema (plus one timeless black void) but also the six Buddhist senses: sight, hearing, smell, touch, taste, and mind. Cinematographer Dong Jingsong is more than up for the task, giving each of the film’s chapters a distinct visual identity that contributes to its sense of romance and epic, century-long sweep.

First, Dong recreates the hand-tinted, hand-cranked look of silent-era film for the film’s opening chapter, which sets the playful, magical-realist tone with paper flowers and a spinning zoetrope. Next is a silvery tribute to midcentury film noir, followed by a still, snowy interlude at a Buddhist temple in winter. From here, we get a self-contained short film in realist ‘80s arthouse style, followed by a neon-soaked trip to the stylized languor of late-’90s Hong Kong.

The thing that ties all of these segments together is a series of tracking shots, which range from jaw-dropping feats of camerawork (a winding 30-minute one-take through a crowded karaoke bar) to smaller, more ephemeral moments (a brief shot following the film’s lead actor through the reflection of a puddle on the sidewalk).

The enigmatic “Other One,” an eternal being who shepherds the film’s “deliriant” through each of these cinematic “dreams,” speaks of the “ancient and long forgotten language of cinematography.” But, if Dong’s work on this film is any indication, that language is as alive as it’s ever been. –Katie Rife

Cinematography, Fabian Gamper, “Sound of Falling”

There’s a timelessness to the image in Mascha Schilinski’s extraordinary multi-character, time-hopping drama following four women in the same family spending time in the same countryside estate at different points over the course of a century. In these spaces charged with collective history and individual pain, the camera of cinematographer Fabian Gamper glides around artfully observing the evolving human conflict, yet not in an entirely inconspicuous manner. At times the characters look back, staring at the lens as if acknowledging its presence, or perhaps using the camera as a portal to communicate with their relatives in the other time periods, who are experiencing similar feelings of frustration and despair.

Coated in soft light, the frames in Schilinski’s masterful film appear as if they existed in the present and the past simultaneously, like photographs plucked from an old album and brought to life. Though the lighting choices are delicate, almost ethereal in sensation, Gamper’s dynamic presence (including in a dreamlike underwater sequence) also acts as a unifying force, even as the narrative walks in and out of each thread weaving them into a devastating whole. That Gamper and Schilinski are married may have also influenced the synergy between content and form magnificently exhibited here. –Carlos Aguilar

Screenplay, Eva Victor, “Sorry, Baby”

Eva Victor’s “Sorry, Baby” takes on a fresh perspective in demonstrating that trauma and our navigation towards healing are anything but linear. In their viscerally vulnerable and naturalistically funny debut screenplay, Victor adopts a non-chronological approach to focus on their lead character, Agnes, and her healing process following being sexually assaulted—which is described as “the bad thing”—by her professor. With Victor’s non-linearity over a five-year period, “Sorry, Baby” structures itself as the aftermath of a traumatic event in which the affected person is slowly catching up, if not stuck, as the world moves on. While “the bad thing” is specific to Agnes and her experience, Victor’s powerful script strikes a universal notion in the challenges people face to reclaim their agency and autonomy following a spiritually breaking traumatic event.

Victor deftly strikes a balance between guiding this challenging subject with empathy and potent comedy with profound, sharp dialogue. Much of it—specifically the complex discussions Agnes shares with her devoted best friend Lydie or Pete, a random sandwich shop owner who helps her calm down from a panic attack—has lingered in my mind since my first viewing at this past Sundance Film Festival.

However, the script of “Sorry, Baby” is a potent indicator that an original, honest, intelligent voice has arrived in Eva Victor. And I await more of what’s in store from their pen in the future. –Rendy Jones

Costume Design, Trish Summerville, “Weapons”

You never forget your first time meeting Aunt Gladys in “Weapons”. Exquisitely portrayed by Amy Madigan in a killer performance that splits the difference between bloodcurdling and outrageously hilarious, Aunt Gladys enters a school principal’s office dressed to the nines in her very own unapologetic way. She’s in a color-blocked tracksuit embellished with floral pins, flaunting her oversized green shades and an enormous tote she might have made herself using a vintage rug. (In fact, the purse is supplied from Max Carpetbag Works.) It’s an instantly legendary look—so memorable in fact that it become among 2025’s popular DIY Halloween costumes—one that costume designer Trish Summerville brought to life in divine detail, complementing (and even informing) both the deliciously kitschy nuances of Madigan’s performance, and the film’s tricky overall tone that serves up uncomfortable laughs and horrors seamlessly.

As the witchy Pied Piper-esque houseguest that overstays her welcome and gets busy threatening an entire community, Aunt Gladys is somehow never too busy to adorn herself in magenta skirt suits, floral house robes, or unthinkable colorful ensembles that look like well-preserved relics of the bygone ‘70s and ‘80s, with subtly modern twists here and there. In Summerville’s costuming (that is equally detailed and lived-in across the film’s other characters), Gladys is both that weird porcelain doll-collecting auntie you’ve learned to avoid in family gatherings (come to think of it, she looks like one of those dolls herself), and a new horror icon that will continue to decorate our most unsettling nightmares.

Editing, Sara Shaw, “Splitsville”

When people discuss the art of editing in movies, the talk too often tends to focus on big elaborate sequences involving action and violence. However, editing also plays an equally important, if often overlooked, part in the success of screen comedies—even the most brilliantly conceived and performed bit of humor can be botched by some hiccup in the process, such as using the wrong angle or cutting to and from the punchline either too quickly or too slowly. In 2025, no film had me laughing louder or more consistently than “Splitsville,” the wild relationship comedy about the conflicts that arise between two couples, one (played by co-writer Kyle Marvin and Adria Arjona) who are in the process of getting divorced and the other (played by director/co-writer Michael Angelo Covino and Dakota Johnson) in an open marriage, and while the screenplay, direction and performances are all quite funny, it is the editing from Sara Shaw that really sends things into overdrive with her ability to know how to handle each moment in just the right way in order to maximize the laughter.

This is most evident in the instantly famous sequence where the two guys end up in an extended brawl that winds up leveling much of the lavish beach house where they are staying, one of the most inspired bits of physical comedy to come along in some time and one that Shaw miraculously manages to keep from slipping into mere brutality. However, Shaw also manages to use her craft to get big laughs in plenty of other ways, from unexpected displays of full nudity to conveying passages in time to any number of surprise reveals. Considering the indifferent manner in which too many comedies are assembled, to see one put together with the grace and skill that “Splitsville” has been given is a cause for celebration, one that will have you rolling on the floor with laughter at the same time. –Peter Sobczynski

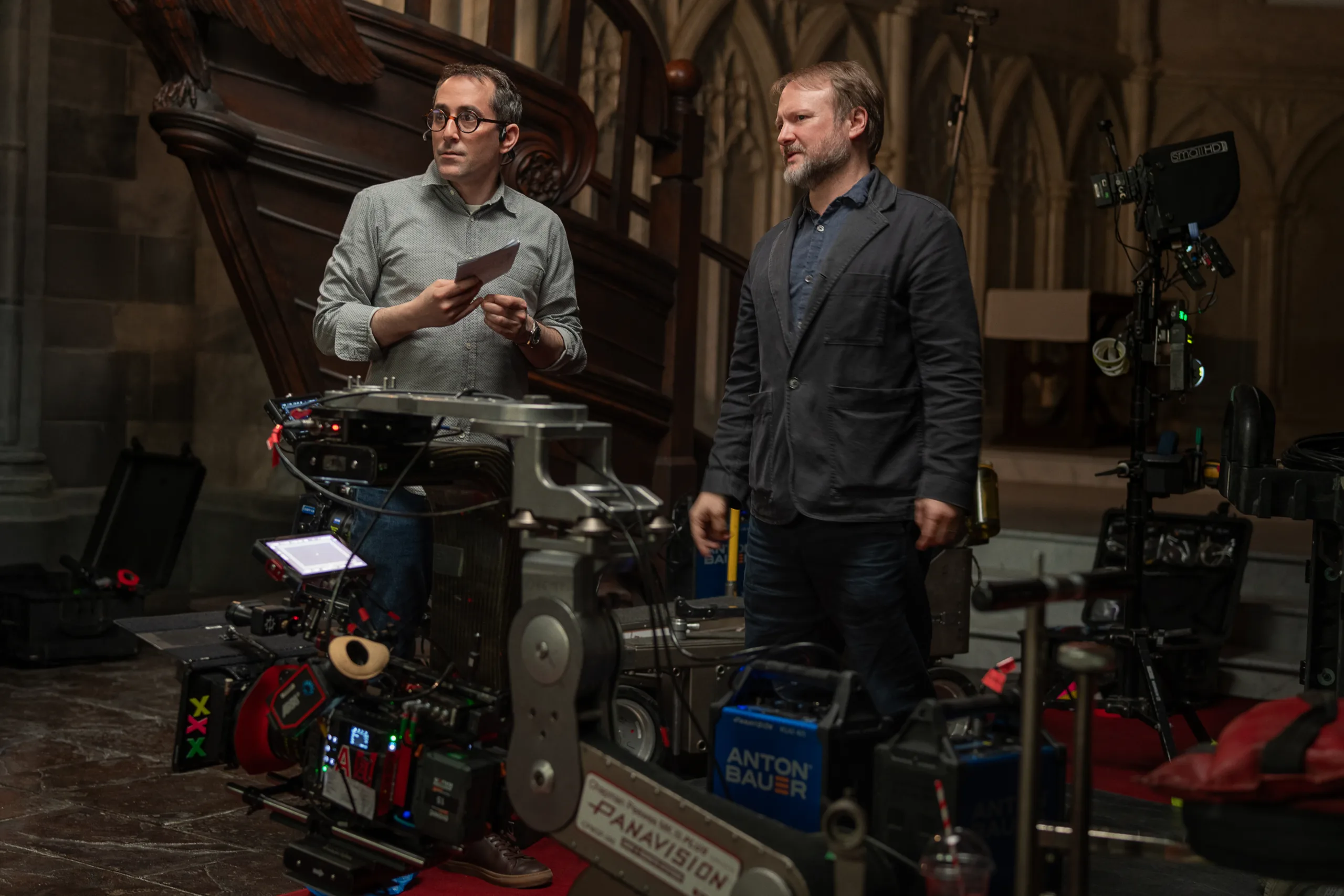

Production Design/Cinematography/Gaffer Team, “Wake Up Dead Man”

The shining moments in “Wake Up Dead Man” are a craft conundrum. At first, you wonder if the tricks of light originate in Rick Heinrichs’ production design. The sanctuary of the fictitious Our Lady of Perpetual Fortitude is gorgeously gothic, every arch and pew evocative. And yet, Steve Yedlin’s cinematography whispers secrets, draped in darkly alluring mystery. Then again, lead gaffer Dave Smith’s lighting is a practical and poetic miracle. Finally, it dawns on you. The pinnacle of craft in the latest “Knives Out Mystery” isn’t a person, but a beam of light known as “God Rays,” and it’s a culmination of three creatives.

Heinrichs built the church set with light in mind, placing windows and architectural details to channel sunlight and create natural sight lines. Yedlin took that foundation and engineered the look, calibrating cameras to capture the interplay of inky darks, vivid color washes, and contrast shadows with light to highlight details. But it’s Smith’s technical precision that brings it all together. The gaffer team created rigs that allowed them to control the timing and intensity of every beam, allowing the outside world to invade the sanctuary, just as Rian Johnson envisioned.

When Benoit Blanc argues for reason over faith, clouds obscure the sun, but Pastor Jud’s passion brings the sunlight back, flaring the camera lens. Later, during Blanc’s ‘Road to Damascus’ moment, the stained-glass glows, and he’s enveloped in ethereal light. God Rays. The awe we feel in those moments is testimony to the rhapsodic effects of craft in collaboration. –Sherin Nicole

Original Score, Jerry Goldsmith and Christopher Young, “Final Destination: Bloodlines”

One of the biggest surprises of this year is Zach Lipovsky and Adam Stein’s “Final Destination: Bloodlines”. Yes, all of its main characters are destined to die in one gruesome way or another, but the movie has a real naughty fun and thrill with those expectedly horrible death scenes. This depends a lot on Tim Wynn’s electrifyingly dramatic original score, which is definitely one of the crowning achievements of this year.

A lesser composer would simply resort to a lot of blunt noises just for jolting us during those death scenes in the film, but Wynn, who once studied under Jerry Goldsmith and Christopher Young, follows his two legendary teachers’ footsteps with a lot of style, skill, and intelligence. While the overall style of his score is often reminiscent of Young’s gleefully grand horror score for “Drag Me to Hell” (2009), its occasionally propulsive moments take us back to Goldsmith’s several notable action/thriller movie scores such as “Basic Instinct” (1992). In addition, he even adds a respectful nod to Shirely Walker’s score for “Final Destination” (2000) during a key scene featuring one of the last performances by late Tony Todd, who played a recurring character throughout the franchise.

Overall, Wynn utilizes well this big opportunity which may boost his career a lot, which was started in the 1990s but mostly consists of a bunch of TV works and video games such as “Warhawk”. Just like Bear McCreary did in “10 Cloverfield Lane” (2016), he suddenly comes to us as another promising film music composer to watch, and the success of “Final Destination: Bloodlines” will possibly lead to him to more opportunities to demonstrate his considerable skill and talent. –Cho Seongyong