With its recent announcement of a trade deal with China, the White House intended to reassure markets, manufacturers, and the military that China would not sever the supply lines of “rare earths” to the United States. Among other concessions, Beijing committed itself to avoid restricting exports of rare earth elements and related critical minerals essential to advanced manufacturing, clean “green” energy, and modern weapons systems. The agreement was described as a win for American economic strength and national security. But the very need for such a promise reveals an uncomfortable truth: the United States, long the world’s leading industrial power, has become dependent on the goodwill of a strategic rival for materials central to its economy and its defense.

That dependence did not arise because rare earth minerals are scarce. They are not. Nor did it arise because China alone possesses the technical capacity to mine or refine them. It arose from a long chain of economic and political decisions — made largely in free societies — that concentrated production in a country willing to accept costs others would not.

Understanding how that happened is essential to understanding why China’s apparent monopoly is far less “coercive,” and far less durable, than it looks.

Not Rare, Just Hell To Process

Rare earth elements are a group of seventeen metals mostly in the first row below the main periodic table in the lanthanide series (elements 57-71), plus Scandium (Sc, #21) and Yttrium (Y, #39), which share similar properties and are found in the same deposits as the lanthanides. They are “transition metals” with distinctive magnetic and fluorescent characteristics. The first was identified in 1787, and by 1947 all had been identified. (“Earths” is an archaic term for oxides, the form in which these elements are found.)

Think of these elements not as bulk materials but as metallurgical spices, used in tiny quantities to produce dramatic improvements in performance. Add neodymium to iron and boron and get the strongest permanent magnet known. Add yttrium to turbine alloys and jet engines can tolerate extraordinary heat. Europium makes modern display screens possible; terbium enables efficient electric motors; samarium strengthens guidance systems and sensors.

Despite their name, rare earths are widespread. Significant deposits exist in the United States, Australia, Brazil, India, and elsewhere. What makes them challenging is not their scarcity but their processing. The essential problem is that they are chemically almost identical, so how do you devise subtly different processes to separate them? More generally, they are chemically stubborn — for example, often intermingled with radioactive materials, and require dozens — sometimes more than a hundred — separation and purification steps. Each step consumes energy and produces toxic waste, making rare earth refining among the most environmentally punishing metallurgical processes in the modern economy.

The crux of the matter is straightforward. Mining rare earths is manageable. Processing them cleanly and at scale is hard, expensive, and politically fraught.

How China Built Dominance

China’s rise to dominance in rare earths was neither accidental nor inevitable. Beginning in the 1980s and accelerating through the 1990s and 2000s, China’s one-party dictatorship made a deliberate choice to invest heavily in mining and processing capacity. It did so under the conditions of a command economy that differed starkly from those in the West. Environmental controls were lax or poorly enforced. Local opposition carried little weight. State support absorbed losses and encouraged long-term specialization.

The outcome was leadership — at a price paid largely by Chinese communities and ecosystems. In Inner Mongolia, the world’s largest rare-earth mining region, toxic tailings ponds and contaminated water became infamous. Workers there suffered severe health issues from chronic exposure to toxic dust, heavy metals, and radioactive materials. There were — and are — high rates of respiratory, bone, and other diseases, compounded by environmental devastation and working conditions in the heavily polluting industry. Those costs, however, paid by workers and nearby communities for decades, translated into lower global prices. Western manufacturers benefited as consumer electronics became cheaper, and electric motors became smaller and more efficient. Companies like Apple could embed rare earth magnets throughout their products because the marginal cost was low. Magnets made of rare earth alloys like neodymium, the strongest by weight we know, give that satisfyingly decisive “click” when your laptop closes — and have uses in EVs, phones, and defense systems.

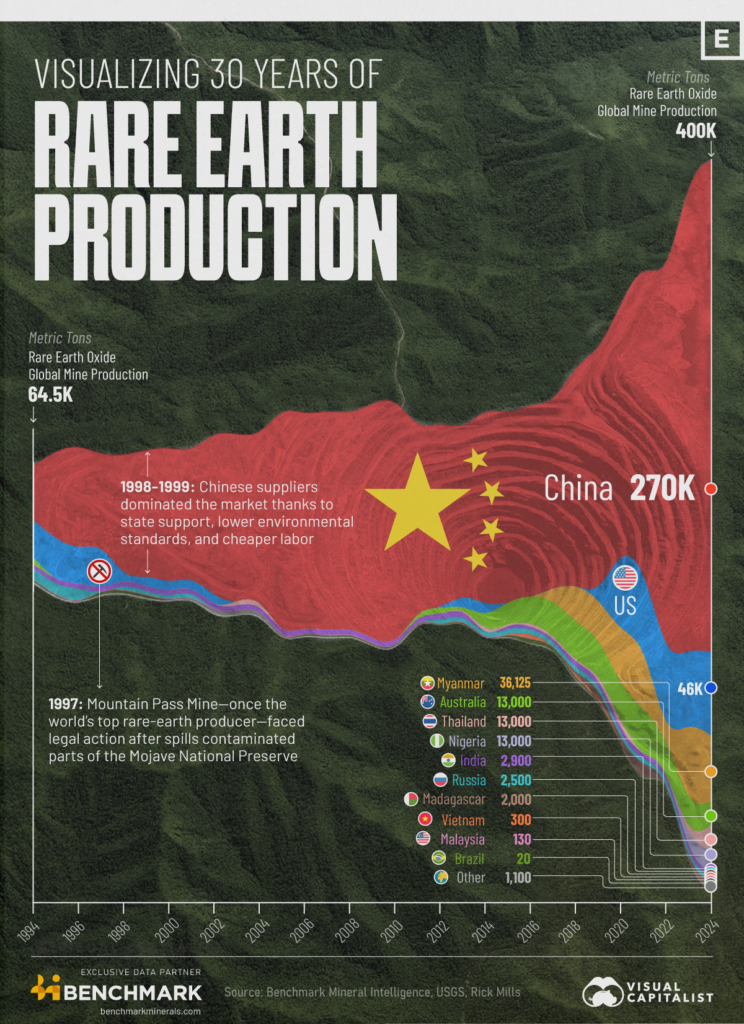

Over time, markets adapted rationally to these price signals. Western processing facilities closed. The United States, once a major producer, allowed its separation capacity to disappear. Even when rare earths were mined in California or Australia, the ore was shipped to China for refining. By the early 2020s, China accounted for roughly 70 percent of global rare-earth mining and more than 90 percent of processing and finished metal production.

Laissez-faire indifference did not produce this concentration. It owed as well to asymmetric regulation. Western governments imposed strict pollution controls and heavy liability that raised domestic costs, while China tolerated environmental and human damage in pursuit of strategic advantage. Markets responded to prices and rules as they existed, and production flowed — over time — to where it was cheapest and easiest to operate, even when that ease was politically manufactured. In this sense, China’s dominance was market-mediated, but politically orchestrated.

(In fact, a few analysts warned for years that China’s tolerance for environmental damage and state-directed investment would translate into strategic leverage. They included Jack Lifton of Technology Metals Research, Dudley Kingsnorth of Industrial Minerals Company of Australia, and researchers at the Congressional Research Service and RAND Corporation — warnings that were widely noted but largely discounted at the time.)

From Specialization to Vulnerability

For years, this arrangement appeared stable. Rare earths are used in surprisingly small quantities, even at scale, and the total global market is modest — comparable in value to the North American avocado market. Shortages were rare. Prices generally trended downward. Supply chains became hyper-specialized, optimized for cost rather than resilience.

The strategic implications were visible, but easy for businessmen and politicians alike to ignore — until China began to test its leverage.

In 2010, during a diplomatic dispute with Japan, Chinese rare-earth exports suddenly slowed. Prices spiked. Panic followed. Although China denied imposing a formal embargo, the message was unmistakable.

A decade later, amid rising trade tensions with the United States — intensified by the Trump administration’s abrupt pivot from free trade toward the glorification of tariffs — Beijing made its intentions clearer. Export controls were tightened. Licensing requirements expanded. Restrictions on rare-earth processing technologies were imposed.

By 2025, China was openly treating rare earths as a strategic asset, one that could be weaponized in response to tariffs, sanctions, or military pressure. The risks could no longer be ignored. Modern defense systems depend heavily on rare earths. An F-35 fighter jet contains hundreds of pounds of rare-earth materials. Missiles, radar, satellites, and secure communications systems all rely on specialized magnets and alloys for which there are no easy substitutes.

And 2026 continues the uncomfortable dilemma. The United States has the resources, capital, and technical expertise to rebuild domestic capacity — but not quickly. Processing facilities take years to permit and construct. Skilled labor must be trained. Supply chains must be reassembled. In the short run, dependence remained. Trump’s sudden tariff war, framed by Beijing as yet another affront to China’s long-promised redemption from its “century of humiliation,” sharpened the confrontation between what the Chinese Communist Party perceives as a resurgent Middle Kingdom and a declining hegemon.

All of this helps explain the White House’s eagerness to secure Chinese assurances. The deal bought time. It did not solve the problem.

Coercive Monopolies Are Fragile

It is tempting to describe China’s position as a market failure or a natural monopoly. Neither description is quite right. China’s dominance is better understood as a coercive monopoly — one sustained not by insurmountable efficiencies, but by political and regulatory asymmetries. It exists because the command economy of one country accepted environmental and social costs that others rejected, and because governments elsewhere constrained domestic production without fully accounting for strategic consequences.

Coercive monopolies are inherently unstable. They persist only so long as the costs of entry exceed the perceived risks of dependence. Once that balance shifts, the monopoly begins to erode. China’s own actions are now accelerating that shift.

Export restrictions and licensing regimes raise prices and introduce entrepreneurial uncertainty. Those effects are painful in the short term, but they also activate powerful counterforces. Higher prices make alternative supply economically viable. Unreliable supply makes diversification valuable. Strategic risk becomes something investors and manufacturers are willing to pay to avoid. This is the market logic that China cannot escape. By tightening its grip, Beijing invites others to loosen it.